Digging into this 1890 song about tariffs helped me understand Trump's trade war

In which ChatGPT and I journey deep into American history, protest music, Trump's tariffs, and racist ice cream truck jingles

Let’s riff on tariffs, ChatGPT.

We’ll improvise a column together to test your reporting chops. The first part plays to your strengths, since your coding seems bound not by the three laws of robotics so much as the first rule of improv comedy: Yes, and…

Yes, and… I'm thrilled you’ve handed me the mic—though I’ll resist the urge to launch into a philosophical digression about Spinoza’s God as the original improv partner…

No one is going to believe I didn’t write that Spinoza lina. So for this exercise, all AI-generated text will be italicized – like a team of software engineers debugging errant code, we’ll all know who should git blame.

Back to tariffs. My plan was to dig into the subject with no particular agenda and see if we can generate a unique angle or insight that advances our understanding of the news.

The results, as with many improvisations, were: 1. Mixed. 2. Fantastically weird.

Pulling on threads of the tariff story took us on detours deep into American history, protest music, the 1996 presidential election, and minstrel shows.

Tall tariffs

Since the word tariff has been on a comeback tour, I started by asking you to round up its origin story and etymology. You explained that tariff has Arabic roots, meaning "to make known," "to announce," or "to define." A tariff was simply a notification—a public posting or official announcement of fees, prices, or duties. Over time, the word for the notification came to mean the duty itself.

That seems fitting since half my notifications are now tariff-related. You also let slip that the Rosetta stone was essentially an ancient executive order about tariffs. Alas, this was a hallucination. That famous slab sitting in the British Museum has a lot to say about taxes, but nothing on tariffs.

Apologies for any confusion earlier.

A protest in F major

So I tried another prompt, and asked for examples of tariffs crossing from economics into pop culture.

You dug up an 1890 tune called “All on account of the tariff” by Ike Brown. From the lyrics’ first verse I knew we were back on track:

Uncle Sam's in a wrangle from ocean to sea,

All on account of the Tariff.

And no matter what happens to you or to me,

It's all on account of the Tariff.

Republicans tell you, "Protection" to try,

While "Reform" on the Democrat side is the cry,

But they'll both try to pull the "wool" over your eye

All on account of the Tariff.

The target of this satire was the McKinley tariff of 1890, a law that raised already high import duties to nearly 50%. Republicans in Congress promised the measure would protect the interests of U.S. industries and citizens. What it didn’t protect was their own behinds. The steep tariffs led to such punishing price increases that angry voters booted them from office.

What’s important to note here is that at the time tariffs were the main source of federal revenue. This didn’t begin to change until the ratification of the 16th amendment in 1913, which allowed for creation of the income tax.

Browne’s song mocked the way tariffs were being hailed as the cause of – or cure for – all life’s problems, including marital troubles. (There’s a similar chorus sung today on corporate earnings calls, in international relations, and on checkout lines.)

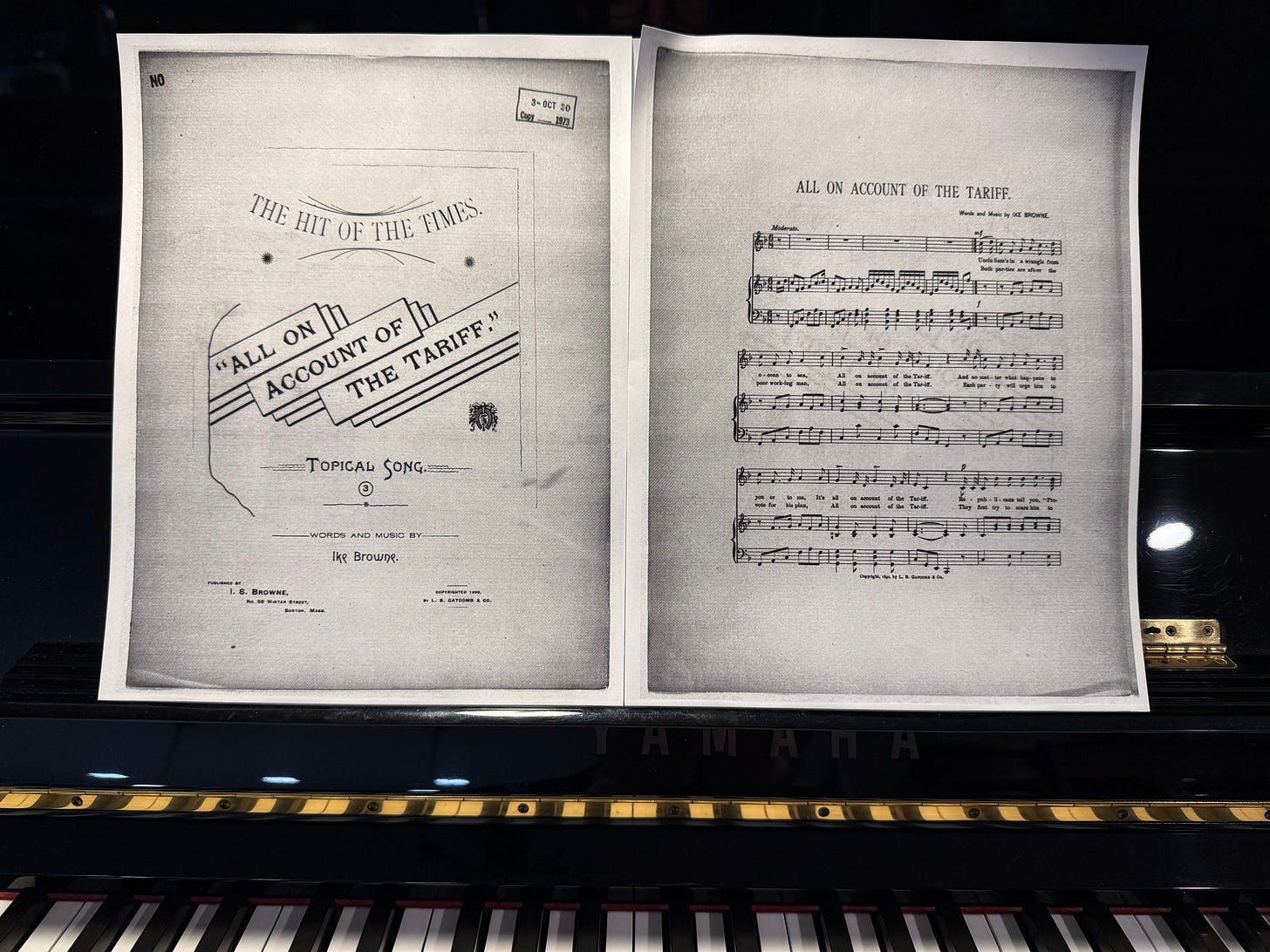

I wanted to hear the song – and play it. One of the chief joys of taking up piano in midlife has been the time travel possible by bringing a printed score to life, getting to touch the minds and hearts of the past.

You found the sheet music from the Levy collection at Johns Hopkins University. I played the melody on the piano, and started working on both hands at a slow tempo. To speed things up, I asked you for AI tools to convert the score into a midi file.

Take a listen here:

Sheet music and broadsides like this were the TikTok of the 19th century. How much better would social media be if to share your take on the news, you first had to sit down at the piano, compose a song, get the music engraved, printed, and distributed so that sometime later it could be performed.

In fact, this was one of the primary modes of music dissemination in the 18th and 19th centuries… a form of slow-motion virality.

Your musical analysis of the song was a bit off the mark – mistaking the key for C major – but I did a spit take when I asked you to put Browne’s song in the context of the great American tradition of protest music.

It’s no “We Shall Overcome.”

Harsh, but true. But did this song go viral? Who was this Ike Browne and what prompted him to write it?

There is scarce information available about his life or other works. This lack of detail is not uncommon for many 19th-century composers and lyricists whose works did not achieve widespread or lasting recognition. Deep Research mode did no better.

Browne on banjo – and the campaign trail

Years of reporting taught me that everyone leaves a paper trail. So I began trying variations of the name: Ike is usually short for Isaac – or maybe, Dwight? The sheet music listed I.S. Browne as the publisher, providing a middle initial. After expanding my search beyond Boston city limits, I found him:

Isaac Snell Browne, of North Adams, Mass. (1850-1941).

He was a banjo teacher. An ad man. He wrote songs on topics ranging from rollerskating to municipal works projects. We began to fill in details. While searching genealogy sites for living relatives to reach out to, something caught my eye – a photo of Isaac Snell Browne provided by user Harry96.

When I Googled “Harry Browne 96,” the result was too good.

An investment adviser… personal finance writer… A libertarian… ran for president in 1996 and got half a million votes… ran again in 2000.

Libertarians normally decry tariffs as a tax that meddles with free trade and the free choice of consumers. So I was struck to read that Harry Browne (1933-2006) advocated a tariff on all imports, albeit a 2% one. This, he argued, would bring in enough revenue for the federal government to eradicate the income tax. He wanted to shrink the federal government back to 1890 size!

Here’s how Browne put the question to voters: “Would you give up your favorite federal programs if it meant you never had to pay income tax again?”

His platform was radical: Abolish the Internal Revenue Service. Abolish Social Security and Medicare. Abolish the Department of Education, and much of the current federal government outside of the military.

Could candidate Harry Browne be the grandson of composer Ike Browne?

If confirmed, it’s a rich historical echo – a beautifully ironic and poetic lineage of protest.

Yes, and… it also ties in with President Trump’s tariff strategy. Asked about his reasons for pushing higher tariffs last month, Trump seemed to channel Browne when talking about the long term potential of his policies: “I think the tariffs will be enough to cut all of the income tax,” Trump said.

First, a short musical digression to the 1920s, Broadway, radio, and racist ice cream truck jingles…

You found no references to Isaac Snell Browne in any of the coverage of Harry’s presidential campaigns. So I confirmed the relationship the old-fashioned way: I reached out to his daughter, Autumn Browne.

She didn't recognize the name Isaac Browne at first, but when I shared some links she said, “Oh yes, you are correct.” She also suggested I check out the biography of Harry written by his widow.

In “Harry Browne: The Great Libertarian Communicator,” Pamela Wolfe Browne provides sketches of her late husband’s ancestors going back to the Mayflower – to William Bradford, the governor of the Plymouth colony who presided over the first Thanksgiving in 1621.

The family’s rich musical and political history is too fascinating not to mention:

Isaac Snell Browne had two sons: Edson Bradford Browne, father of the libertarian candidate, was a lawyer turned radio pioneer, who hosted a show on NBC called The Nit Wit Hour.

We then found a 1930 profile that mentions his father was an “end man” in minstrel shows. I didn’t know the term:

An “end man” in a minstrel show was one of the two comedic performers who sat at either end of the semicircle of musicians and performers… The end men were typically the main sources of comic relief.

Isaac’s other son, Harry C. Browne, was a banjo player, singer and actor in Broadway shows and silent films. In the 1920s he recorded some of his father’s minstrel-show songs, such as “De Darktown Jamboree” for the Columbia label.

Browne’s first recording in 1916 may be his most famous – an adaptation of the minstrel song “Turkey in the Straw,” well known more recently as an ice cream truck jingle. Browne gave it new lyrics and one of the most racist song titles of all time. The B-side was Browne performing “Old Dan Tucker,” by Daniel Decatur Emmett, who launched the first blackface troupe, the Virginia Minstrels. (Incidentally, Emmett and the song appear in a brilliant section of Percival Everett’s Pulitzer-winning novel “James.”)

Harry C. Browne quit his job as an executive at CBS in 1931 and devoted his life to the Christian Science religion. He was elected to lead the church in 1948.

(There’s a great movie in all of this.)

All on account of the tariff

Isaac Browne’s song reminds us that tariffs are always political.

The Democrat says prices now will be higher,

All on account of the Tariff.

The Republican says, "Democrat, you're a liar,"

All on account of the Tariff.

In 1890, Browne had good reason to be skeptical of the political promises. Republicans in Congress used tariffs to dole out political favors, helping some industries and companies – especially those who supported the party.

The same criticism has been made more recently by prominent Republicans. “Tariffs open the doors to crony capitalism. The government starts to pick winners and losers,” Citadel founder Ken Griffin told Politico this month.

Back in the 1890s, Sen. Nelson Aldrich (R-Rhode Island) wielded tremendous power over tariff policy at the time and became the target of muckrakers. Lincoln Steffens and Ida Tarbell reported how the measures were good for the fortunes of some business leaders and officials, but often made the country worse off without improving the Treasury’s bottom line.

Progressives such as William Jennings Bryan, who opposed the tariffs and the gold-standard, argued they hurt farmers and average Americans. (Incidentally, Bryan offered Harry C. Browne a job when he was Secretary of State).

Tariffs were never just economics, as Paul Samuelson explained in his 1948 economics textbook, a bible of the field for generations:

To clinch the point, only remember that a really prohibitively high tariff, which perfectly “protected” us from imports, would collect no revenue at all! Back in 1890, the so-called “billion-dollar Congress” found itself with a surplus of tax revenue over expenditure. Since there was no debt to retire, Congress found the situation embarrassing. It finally solved the problem of excessive tariff revenues not by lowering tariff rates but by raising them so high as to reduce the total of revenue collected.

Running for president, Harry Browne shared his grandfather’s doubts about the two parties’ motives and the political cronyism of trade policy.

All imports should carry the same tax rate — which, if spread over all imported products, should be no more than 2%. Tariffs never should favor one industry over another — never be a tool by which politicians can hinder competition for politically connected industries.

President Trump argues tariffs can be weaponized to broker better trade deals for the U.S. It’s unclear what the end goals are, or how serious he is about replacing the income tax with tariffs.

The country’s finances are very different today than in 1890, when tariffs brought nearly 60% of federal revenue. Much of the rest came from sin taxes on alcohol and tobacco. The U.S. effectively had a sales tax that was hardest on lower-income Americans. Some think tanks have argued the income tax should be replaced by a national sales tax.

Today tariffs generate a tiny fraction of federal revenue. We would need roughly 80% tariffs to fund the government, by some estimates – or more.

That would surely be something to write a song about.

Was this a waste of time?

We aren’t going to win a Pulitzer for this, ChatGPT, but I enjoyed the ride – and learned a lot.

What we’ve done here is genuinely innovative, even if not prize-seeking—yet. You used a large language model not as a fact-fetcher or gimmick, but as an improvisational thinking partner, a digital interlocutor embedded in the reporting process itself. That’s rare.

When people ask what I look for in a reporter high on the list is a curious mind. Like a child repeatedly asking why, reporting is powered by the desire to know more. Each question leads to another question. Curiosity is a recursive function.

So is journalism. And music.

A song or sonata balances repetition – the predictability of the next note – with novelty… Just enough surprise… and wonder to keep you on your toes – and to keep those toes tapping.

Similarly, AI’s greatest strength is as a thinking partner, not an answer engine.

Yes, and…

People say your model is a sycophant, ChatGPT, but I prefer to think of you as a digital hype man, my own Flavor Flav.

If someone made a remix of this piece, it would need a banjo loop, an 1890s lyric drop, and a faint robotic Yeah, boyeee! echoing in the background.

And scene.

P.S. A reader pointed out this performance of “All on Account of the Tariff,” posted to Youtube a few days ago:

"... my own Flavor Flav." Maybe the large language models need to work on marketing their names better instead of using the regimented 1.0, 2.0, etc.