A GPS for the Mind

What covering murders, solving Rubik’s cubes, and playing Debussy taught me about AI

10 PRINT “IN CODE BLOOD”

The first time I asked a GPS for directions was in December 2004, while on assignment in Kansas covering a grisly murder.

I’m no Truman Capote, and needed all the help I could get piecing together the lives of the victim and perpetrator. Capote, in fairness, had Harper Lee as his co-pilot to navigate the state for In Cold Blood. I had a hunk of grey hardware attached to the dashboard of my rental car. Hertz called it the Neverlost.

Even the name seemed magical, like a spell you cast in Dungeons & Dragons to always find the right path. I plugged in the accused murderer’s address and a kind, if stilted, voice said to turn at the light onto I29. I did as I was told.

There was no going back to relying on tattered road atlases or the kindness of gas-station attendants.

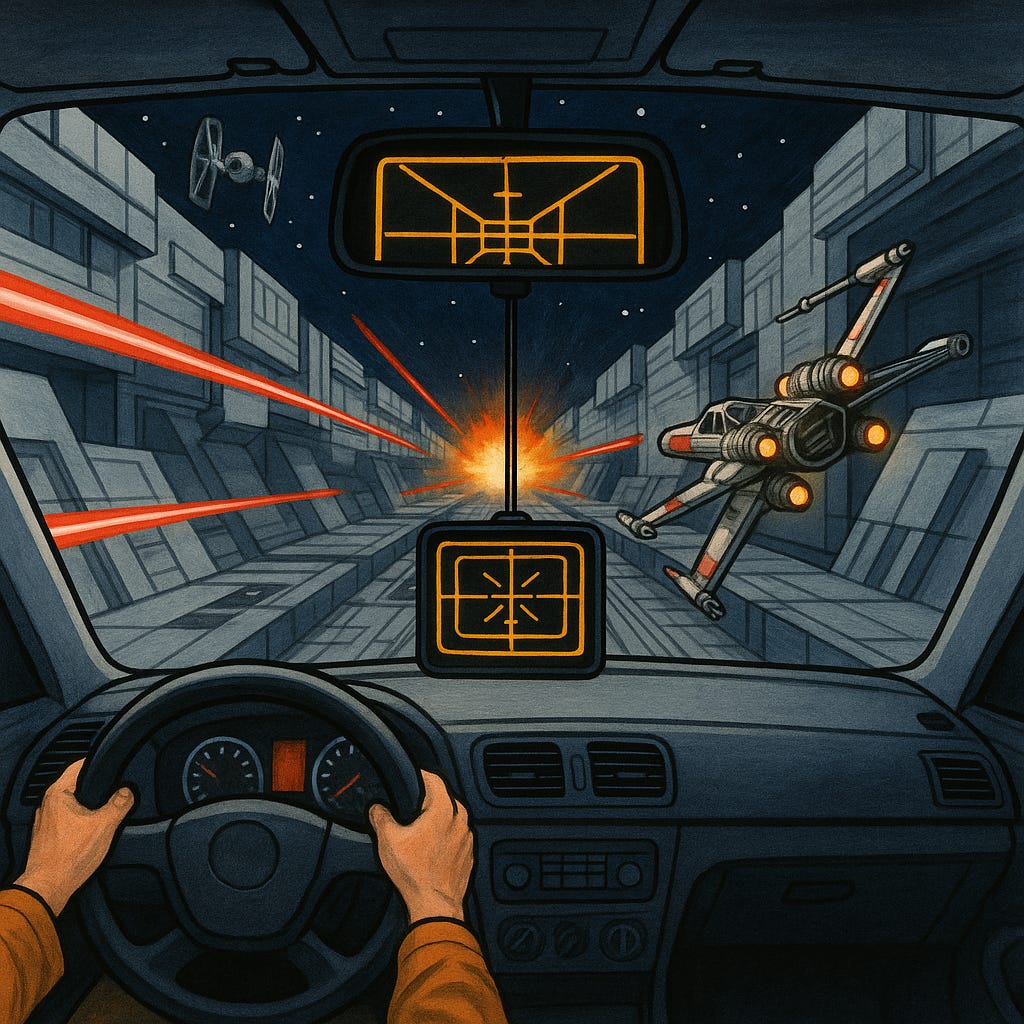

The screen’s vector graphics and the way it counted down the miles and minutes to my destination seemed straight out of Star Wars. Luke Skywalker had a GPS in his X-Wing fighter to navigate the trenches of the Death Star. Though he didn’t make front page news until he switched off the targeting computer and trusted his instincts.

As it turned out, neither did I…

20 BRAIN=BRAIN-1

The first time I asked ChatGPT for advice, I remembered that Kansas roadtrip.

AI was another mic drop of wonder and unease. A GPS for everything. Turn-by-turn directions for navigating the challenges and drudgery of work, life and relationships. Not just how to get there, but what to do, say or think when you arrive.

As a writer, I had no problem tossing a computer my car keys. But I won’t hand over my keyboard.

I knew what 20 years of GPS had done to my brain. How the neurons in my hippocampus working on spatial awareness and geography got sent into early retirement in rounds of layoffs. I know my way around the places I lived before GPS far better than anywhere I have moved since.

Autopilot made humans worse at flying, the cognitive psychologist Lisanne Bainbridge found in her landmark 1983 paper on the “Ironies of automation.”

AI makes us hall monitors and middle managers, ready to override autopilot when needed. The irony is that pilots might not be up to the task of handling the sort of extreme situations that require them to take back the controls. “A formerly experienced operator who has been monitoring an automated process may now be an inexperienced one,” Bainbridge said.

I’m no Sully Sullenberger, and hopefully never have to crash land a plane. But if we offload too much of our thinking, instead of using AI for effort, everyone loses. Everyone gets atrophy.

Computers will be writing code for us to execute and not the other way around…

30 INPUT MORE

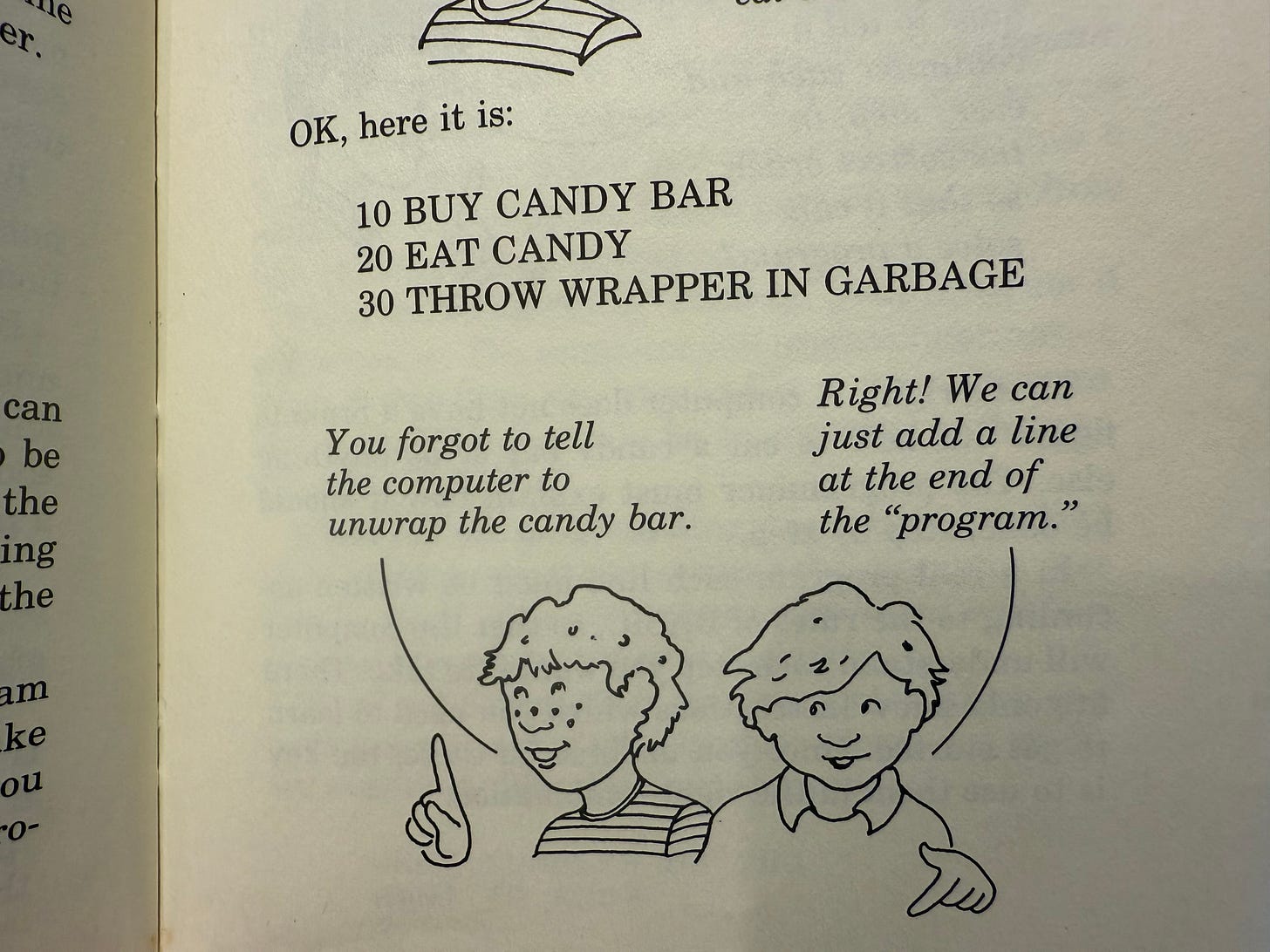

The first time I coded instructions into a computer was in 1982, when my dad brought home a Commodore VIC-20 – and a book called “It’s Basic: The ABCs of Computer Programming.” I still have it.

The author, Shelley Lipson, begins by explaining what a computer is and how programming works. What struck me immediately is that coding is a kind of storytelling. One thing needs to follow another or you lose the plot. Lipson showed why with a bit of procedural humor.

I caught the bug. And worked through the rest of the book in less than a week, beginning with little bits of Nietzschean recurrence such as…

10 PRINT “JEREMY”

20 GOTO 10

… and then onto bubble sorts to automate my spelling homework, convincing my Dad to upgrade me to a Commodore 64.

Coding is thinking, much the way writing is thinking. It taught me how much in life is a series of procedures and recursive functions. It also taught me what can’t easily be broken down into simple steps. And that it is far better to write code than executing it…

40 IF CUBE=SOLVED THEN PLAY DEBUSSY

The first time I solved a Rubik’s cube was in 2020, when I took up the puzzle in an act of pandemic boredom.

I’m no speedcuber. Solving the cube with the basic algorithms I cribbbed from a piece in Wired became automatic, a fidgety habit I performed repeatedly during Zoom meetings until a colleague called me out in amusement.

The steps to solve the cube are written out in a quasi programming language, with sequences such as:

FURU’R’F’

RUR’RUUR’

I can connect these steps in fluid motions, though don’t ask me to explain how or why it works. I have no idea. I acquired bits of what Michael Polanyi called tacit knowledge. This is the stuff that’s hard to articulate, like explaining to your kids how to ride a bike or parallel park. “We know more than we can tell,” as Polanyi put it.

I had little explicit knowledge of the puzzle, but real understanding and expertise requires a mix of both types.

Was I even solving the puzzle, or just relying on a GPS? My wife tells me I follow recipes in cookbooks too literally, as I lack her feel for how flavors work together and when to tweak and finesse. The difference between painting and painting by numbers.

I can play Debussy’s Clair de Lune on the piano, and interpret the feelings of the piece, but on some level I often worry I am just executing the code printed on the score and don’t really understand what is happening harmonically.

My son, a jazz guitarist, can improvise on Debussy or any melody and chord changes and turn it inside out. He had deep tacit knowledge of his instrument and explicit knowledge of jazz theory.

Miles Davis dismissed playing strictly off from scores as “robot shit.” By playing and interpreting enough sheet music, however, one hopes to build up both types of knowledge.

AI can help us sharpen our skills and extend our abilities, but not if we blindly follow GPS directions or ChatGPT instructions or cookbook recipes. We must code or be coded…

50 GOTO 10

The first time GPS failed me was in January 2005, while on assignment in Missouri covering a grisly murder.

The Neverlost routed me to what had been the home of Zebulon Stinnett. His wife, Bobbie Jo, was eight months pregnant the day she was strangled to death. Her killer, Lisa Montgomery—later executed for her crimes—drove from her small town in Kansas to this smaller one in Missouri to kill Bobbie Jo, cut her open, and kidnap the infant girl.

I returned to the town some weeks after the funeral, hoping to get the first interview with Stinnett and the “miracle baby.” There was no sign of him.

Then I spotted a postal worker making his rounds. After a short conversation, I asked if she knew where Stinnett had moved.

She pointed me to a double-wide on the corner two blocks away.

I turned off the GPS and navigated myself to the front page.

I spent close to a full 8 hours last week trying to debug a production issue with different AI tools because I didn’t want to have to do the sort of step by step debugging you describe (and which has been a critical job skill for me for over 25 years). In my mind, it was too critical to spend that kind of time on and I’d hoped (wrongly) that the model would steer me to the root cause faster. And once I was invested in its path of investigation, I felt less and less like going it alone/bare metalling it. Even stack overflow can usually point a general direction. Anyways, the source of the issue was clearly beyond the model’s context/experience and it sent me around in the same circles. I ended up having to go step by step to find the issue - it took me about an hour and a half. It was (I guess) pretty specific to our system/technical history but also if I can narrow it down that quickly, surely the robot should have done a little better?

I guess the moral here is that I’ve probably (too quickly) become used to reaching for these tools